Inquiry learning is recognised by prominent educational researchers, such as Harada and Yoshina (2004) and Maniotes and Kuhlthau (2014), as best practice pedagogy. Accordingly, the Year 10 History assessment task will be critically analysed and recommendations made for future improvement to ensure the students are experiencing authentic inquiry learning experiences.

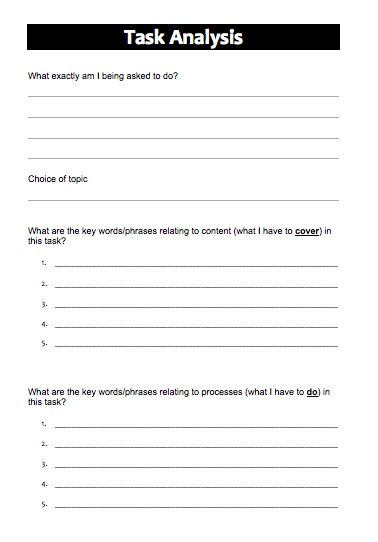

The assessment task was undertaken in Semester 1 of the school year by all students within the cohort as a formal assessment task, which contributed toward their final grade. It was a ‘coupled’ inquiry, in that it was both teacher and student directed (Lupton, 2015). Specifically, the classroom teachers chose which significant events of WW2 and their related long term consequences students should examine, whilst the students were empowered to pose their own inquiry question and conduct their own research, with the support of the research booklet and teacher guidance. This form of inquiry was well suited to the Year 10 cohort, providing students with a scope and boundaries whilst allowing them the autonomy to choose a topic of interest and conduct their own inquiry independently. For the majority of the students this was the first time they had experienced such independence in an inquiry task and they gained new skills and knowledge.

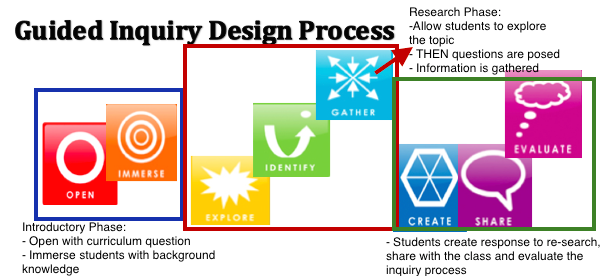

According to Kuhlthau (2010, p. 4) “guided inquiry is planned, targeted, supervised intervention throughout the inquiry process”. Therefore, it is important to note that each classroom teacher had various knowledge of how to conduct a guided inquiry, particularly during the critical ISP stage.

Image created by site author: adapted Inquiry Model Diagram Perspective 2: Maniotes and Kuhlthau. (2014). p. 12

Thus, the students in each class received differing degrees of intervention and scaffolding based on their teacher’s ability to run authentic guided inquiry sessions. These inconsistencies in conducting the assessment task significantly impacted each student’s learning experience, particularly during the ISP where students need the most guidance and support from their teacher (as discussed in the ILA Findings).

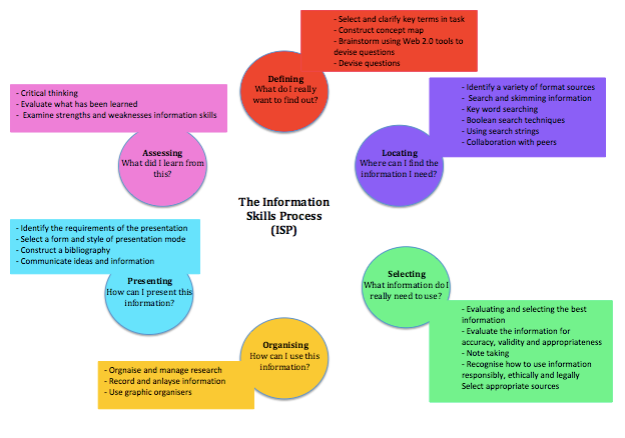

Image created by author: Information Search Process Model by Kuhlthau, C. (2004). Information Search Process.

The task utilised a variety of questioning frameworks that guided students through the assessment task. The overarching question of this task was the essential or ‘big question’, ‘what were the short term effects of a significant WW2 event and how did this event have long-term effects to shape the modern world?’ This essential question is open-ended, “designed to provoke and sustain student inquiry”, whilst addressing the significant historical event that is WW2 (Wiggins and McTighe, 2004). Importantly, this essential question acted as a starting point, somewhat of a tree trunk where students then, posed their own inquiry questions off it, as branches.

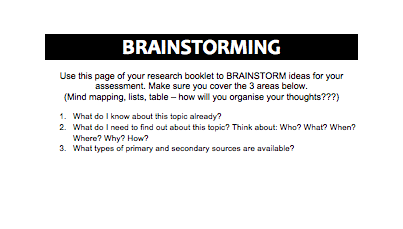

The task applied two generic questioning frameworks that were intertwined to assist students in posing their own inquiry questions under the umbrella of the essential question. These two frameworks effectively led students from the ‘immersion’ phase of inquiry to the ‘explore’. The first generic questioning framework can be considered a modified version of the KWL (Ogle, 1986). That is, during the ‘immerse’ phase the research booklet prompted students to brainstorm and pose questions about:

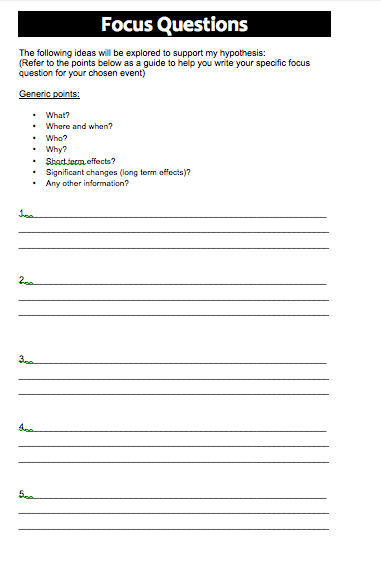

This framework was a sound starting point for the students as many found posing their own questions overwhelming without a scaffold. The assessment task allowed students to “test the waters” of the questioning and thinking processes involved in inquiry learning and enter the ‘explore’ phase of the ISP by completing background research, preparing them to enter the ‘identify’ stage where the students posed their own hypothesis and inquiry questions related to the short and long term effects of their chosen WW2 event. This effective scaffolding effortlessly guided students into the fundamental second generic questioning framework within the task. This questioning framework was another modified structure based on the 7W’s encouraging students to pose their own inquiry questions related to their hypothesis as seen below.

Granted that both of the generic questioning frameworks did have a slight hint of historical questioning, such as asking students to consider what primary and secondary sources they may find throughout the inquiry and what were the significant changes of the event, these were given little emphasis in the overall questioning framework which was disappointing considering that it was a history assessment task. However, the positioning of the two generic questioning frameworks within the inquiry was a significant feature of the task, demonstrating that it was a genuine inquiry learning activity. An authentic inquiry assessment task are “those in which students answer their own questions” and when the “research question or thesis statement comes toward the middle of the research process after exploration and before collection, rather than at the beginning” (Bell, Smetana and Binns, 2005 and Maniotes and Kuhlthau, 2014, p. 10). Although the questioning frameworks were generic models based on the KWL and 7W’s they did model to students how to pose their own inquiry questions. This was evident from the findings of the task with all students posing sound inquiry questions with some students even posing questions that were more complex. In regard to the Australian Curriculum the task met all of the requirements as outlined in the description of the assessment task.

Furthermore, within the research booklet students were provided with a critical questioning framework that prompted them to analyse and evaluate the sources and the information they had found. These questions were historically based in that they encouraged students to critically examine the source in terms of perspective, motive, bias, reliability and usefulness. These questions provoked the critical thinking skills of the students, it required them to explore the source in depth and think like a historian. This particular questioning framework is fundamental to any historical inquiry, if it had have been excluded from the task than the task could not be truly classified as an authentic historical inquiry. However, some students did not use this framework effectively which will be discussed later in this piece.

There were two significant flaws within the questioning framework of the task 1) it had a limited process questioning framework and 2) it did not encourage an action research cycle, which is a critical element of holistic inquiry learning. Firstly, the task only required students to think about the process that they were undertaking at the very beginning by defining the task. The omission of further process questions during the critical research phases is a serious limitation. According to Maniotes and Kuhlthau (2014, p. 11) the importance of understanding the thinking and emotional process involved in inquiry is essential for students to develop an awareness of the learning process. The students at this particular College have had very little experience in explicit inquiry learning. That is, they have never been taught that “this is the inquiry process and these are the questions you should be considering at each phase”. Without the guidance of a process questioning framework students missed the metacognitive thinking that came with the inquiry and will be less likely to be aware of these thinking process and learning that took place when they conduct further inquiry activities in the future.

Secondly, inquiry should embody a questioning framework(s), information seeking process and an action research cycle (Lupton, 2012). The task encompassed two out of the three critical elements, with two questioning frameworks and an information seeking process. However, the opportunity for students to undertake an action research cycle and pose new questions during their research or from their conclusions was not evident. Thus, the assessment task was rather static and did not “mirror” the everyday processes of inquiry in which students would utilise in their world outside of the classroom (Lupton, 2012). The notion of connecting students’ world is also emphasized by Kuhlthau (2010, p. 5); creating a “third space” is “fundamental” to guided inquiry. That is, guided inquiry should create a learning environment within the third space, where the students’ world outside of school (first space) and their world at school (second space) overlap (Kuhlthau, 2010, p. 5). The exclusion of an action research cycle means that students are not being prepared for action research in professional and community contexts. In this way, they are not yet being empowered to become active participants in workplaces and communities (Lupton, 2012).

The assessment task employed the information skills process (NSW Department of Education and Training, 2007) as the model for students to pursue information.

Image created by site author: Information Skills Process by NSW Department of Education and Training, 2007

The table below compares the information seeking model and the guided inquiry process of the task.

| Information Skills Process | Student processes through out the ILA | Guided Inquiry | Student processes through out the ILA |

| Define | Students were asked to define the task in their own words, brainstorm, conduct background research and pose a hypothesis and inquiry questions | Open | Teacher introduces background to WW2 |

| Locate (ISP) | Research | Immerse | Assessment task was given/ explained and an information seeking session with Teacher-Librarian held |

| Select (ISP) | Collecting sources, analysing and evaluating information | Explore (ISP) | Background research conducted |

| Organise (ISP) | Organising the information, planning and writing the script, and creating an imovie documentary | Identify (ISP) | Formation of hypothesis and inquiry questions |

| Presenting | Present imovie documentary to the class | Gather (ISP) | Research is conducted during ISP with teacher guidance |

| Assessing | No student self-evaluation/assessment. Teacher assessment only | Create, Share and Evaluate | Information is organised, script written, imovie created and presented. Students did not evaluate the inquiry process |

The information seeking model employed by the task during the ISP was one that was effective in developing the information literacy skills of students. As students moved through the processes of this model, particularly the stages of the ISP, they learned “the process of inquiry as well as how they personally interact within that process” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p. 7). At the same time high levels of 21st century literacy were being developed as students were reading to learn and determining the importance of informational texts (Kuhlthau, 2010, p. 8). A limitation within the assessment task was that students were not required to evaluate/assess what they had learned, the learning process or their information seeking skills, resulting in a missed opportunity to develop self-evaluation skills. Despite this, the assessment task did give students the chance to develop critical thinking skills.

The assessment task allowed students to develop critical thinking skills, and in turn information literacy skills, through the evaluation process of the sources that they found. Again, this scaffolding was provided within the research booklet, prompting students to consider an evaluation of their sources and reflect on the information that they had gained from it.

However, during the information seeking sessions it became apparent that some students often did not complete these source evaluations. It is believed that these students overlooked this step as they deemed finding information to answer their inquiry questions more important than evaluating sources, ignoring a critical historical skill. According to Forzani (citied in Herold, 2015), “without good evaluation skills, students develop misconceptions from unreliable and inaccurate texts…we need to focus instruction on critical evaluation, since students are significantly lacking in these skills”. To combat this, students were provided with two choices of source evaluation methods to assist in determining the credibility and usefulness of a source before they collected their information; both evaluation tools emphasised reliability and relevance, which are critical when conducting a historical inquiry. However, Schrock’s model was more prescriptive and was a useful tool for the students as many of their sources were online, allowing them to evaluate the visual, content and authority elements of the source. On the other hand, the CRAP test was not as prescriptive but provided students with ideas for what to look for when evaluating sources. This scaffold was useful once students became skilled at identifying irrelevant sources. Significantly, it must be recognised that students in other classes may not have received these information evaluation rubrics.

Furthermore, the information literacy skills that students gained throughout the assessment task conformed to the situated window of the GeSTE windows as outlined by Lupton and Bruce (2010).

GeSTE Window images from: Lupton, M. (2015). LCN616 Inquiry Learning: Week 2 mini lecture [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved 8th August 2015 from https://inquirymodules.wordpress.com/module3/

The situated perspective of literacy is contextual, authentic, collaborative and participatory (Lupton and Bruce, 2010, p. 5). This window of information literacy is double barrel in that it also embodies generic information literacy, such as search strategies and ICT skills. Within the situated window information was internal and subjective (Lupton, 2015) as students examined the short and long term effects of WW2 through a socio-cultural context, they made their own meanings from what they found throughout the inquiry. That is, the students themselves decided what information was valuable, relevant and useful to their inquiry. The assessment task engaged students in “authentic information practices” to “create new knowledge” through examining the significance of WW2 on the modern world (Lupton, 2015) whilst allowing them to practice generic information literacy skills, including expert search skills and citing sources.

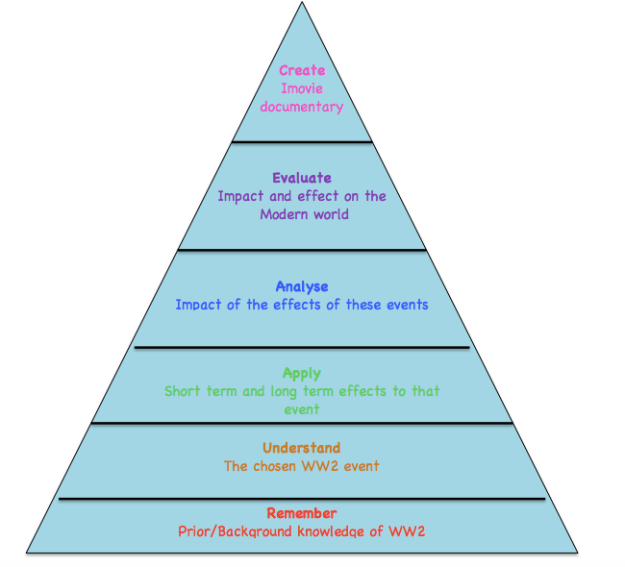

Importantly, the task was well designed to meet the learning outcomes and objectives prescribed by the Year 10 Australian History Curriculum (as seen in the Description of the ILA >Content Descriptors). Through examining the effects of WW2 students were given the opportunity to develop their understanding of a significant historical event that had shaped the modern world whilst developing specific skills within the history discipline. In terms of developing higher order thinking and critical thinking skills the assessment task excels. Specifically, the task engaged the students in all levels of Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised Bloom’s taxonomy from basic remembering of background knowledge to evaluating the short and long term effects of their WW2 event on the modern world, before creating this into a historical argument to share with the class.

Moreover, elements of the assessment task coincided with the Australian Curriculum Critical and Creative Thinking and ICT Capability Learning Continuum.Essentially, the assessment task engaged students in critical thinking by asking them to pose questions in order to analyse a complex issue, assess and explain a range of perspectives and present their findings as a historical argument; whilst employing information technology as an investigative tool and to create meaning from their inquiry. Lee (2014) declares that teachers need to assist their students in developing these thinking skills by self-modelling and teaching them how to critically question. Again, it must be remembered that each class may have received different experiences of this depending on the scaffolding provided by their teacher. Nevertheless, the level of critical thinking that the assessment task required students to engage in was complex and challenging, ultimately improving their learning outcomes in the future.

Recommendations will now be discussed to further improve the quality of the task.

References:

Bell, R., Smetana, L., & Binns, I. (2005). Simplifying inquiry instruction. The Science Teacher, 72(7), 30-33. Retrieved 28th July 2015 from http://cmapspublic2.ihmc.us/rid=1KLP3BZQ7-1PJHFVS-19RV/Simplifying_inquiry_instruction.pdf

Herold, B. (2015). US students awful at evaluating reliability of science readings. Education Week, July 27. Retrieved 8th August 2015 from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/DigitalEducation/2015/04/online_reading_science_study_results.html.

Kuhlthau, C. (2010). Guided inquiry: School libraries in the 21st century. School Libraries Worldwide, 16(1), 1-12.

Lee. M. (2014). The educational fallacy of an ICT Continuum. [Web log]. Retrieved 28th August 2015 from http://malleehome.com/?p=2745.

Lupton, M. (2015). LCN616 Inquiry Learning: Week 1 mini [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved 3rd August 2015 from https://inquirymodules.wordpress.com/module3/

Lupton, M. (2015). LCN616 Inquiry Learning: Week 2 mini [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved 8th August 2015 from https://inquirymodules.wordpress.com/module3/

Lupton, M. (2012). What is Inquiry Learning. [Web log]. Retrieved 8th August 2015 from https://inquirylearningblog.wordpress.com/2012/08/22/what-is-inquiry-learning/.

Lupton, M. (2012). Everyday Inquiry. [Web log]. Retrieved 8th August 2015 from https://inquirylearningblog.wordpress.com/2012/07/27/everday-inquiry-and-inquiry-learning/.

Lupton, M. & Bruce, C. (2010). Chapter 1 : Windows on Information Literacy Worlds : Generic, Situated and Transformative Perspectives in Lloyd, Annemaree and Talja, Sanna, Practising information literacy : bringing theories of learning, practice and information literacy together, Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, pp.3-27.

Maniotes, L , & Kuhlthau, C. (2014). MAKING THE SHIFT. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), p. 8-17.

Wiggings G, and McTighe, J. (2004). Essential Questions: Doorways to Inquiry and Understanding. Retrieved 16th August 2015 from https://inquirymodules.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/mctighe-essential-questions.pdf